Two nights ago, I walked into a sub shop to buy dinner for my daughter. There was a man with a dog. He was about my age and the two boys with him were likely his sons. The dog was a dog – I don’t know if it was a purebred or a mutt. I do know that it was on a leash and had a collar and a nice temperament. What it didn’t have was anything that indicated that it was a service dog or a seeing eye dog. It was clearly the family pet. In a restaurant. With food being prepared just a couple feet away, and multiple tables for customers.

I almost shook with anger.

I wrote last week about my ‘bad wolf’ and my propensity to get angry at strangers who offend my sense of right and wrong.

I was very offended by dog man. I craved confrontation. Not physical. But I wanted to call him out on offensive, inconsiderate, selfish behaviour. It’s a restaurant. For people. Not dogs.

For the last several years I’ve taken an intense interest in what’s often referred to as ‘personal growth,’ ‘self-improvement,’ or ‘wellness.’ I’ve put those terms in quotes for many reasons, including, the billion-dollar industry that lies behind them. Books and podcasts abound – thousands of them – offering philosophies, lists, and tips on how to ‘be your best self.’ The self-help industry is easily, and perhaps justly mocked. But it exists because we are all imperfect, fallible creatures with the capacity to recognize our shortcomings.

I didn’t shake with anger, but I seethed with rage. My instinct was to tell dog man his dog shouldn’t be in the restaurant and he should leave. His boys were teens, or nearly so, and clearly capable of ordering their food and paying for it. I wanted to tell dog man to take his dog outside.

I considered a passive aggressive approach. There were three employees behind the counter. I could have asked, loudly, “are dogs allowed in here?”

I didn’t say or do anything. I just stood, waiting my turn in line. Dog man went to the washroom, taking his dog with him. Weird.

I just wanted a shredded cheese, cucumber and mayo sub for my daughter. I didn’t want a confrontation. I didn’t say anything.

But my inner outrage soared. What if my daughter was with me? Ever since our dog died, she’s battled a fear of dogs. Had she been with me, and this dog approached her, she might have been terrified. Maybe she would have screamed. Maybe she would have hidden behind me in fear.

However, she wasn’t with me. That wasn’t happening. The staff didn’t seem at all bothered by the dog. Hard at work, not one of them seemed to care.

Dog man returned from the washroom. He and the dog hovered near his boys. He asked them if they’d ordered for him. They had.

The boys were quiet. Polite with the staff. Unaware of the angry middle-aged man standing behind them. The first reason I didn’t say anything to dog man was because of those boys. I did not want to embarrass dog man in front of his sons. I did not want to subject them to an uncomfortable, awkward, potentially volatile situation. Like my daughter, those boys just wanted subs for dinner. They wanted an uneventful, quiet, family night.

I recognized this as a moment to test myself. It would feel good, in the moment, in the split second, to confront dog man. To tell him he was wrong.

But was he wrong? Maybe not. I stood there and considered that maybe he wasn’t doing anything wrong at all. If this was France, no one would bat an eye. Maybe I wasn’t mad at him, but at our ever-changing world. When I was a kid people didn’t bring dogs into businesses, or restaurants. Full stop. It wasn’t a thing. At least in Ontario. But I’ve lived on Vancouver Island for close to twenty years now. I’ve seen dogs inside businesses dozens of times. People do that here. Maybe they do it everywhere now.

Maybe it wasn’t unhygienic. A plastic shield protected the food. The dog was just inches off the ground. I was way more likely to get sick from a staff member or customer coughing and sneezing.

Did it matter if he was wrong or I was wrong? This was an opportunity. An opportunity for me to pause, breathe, and not react based on my initial thoughts and feelings. A small and easy opportunity to calm my bad wolf. A small step on the road to living a life where my actions aren’t dictated by what others do and how that makes me feel.

Sometimes that is necessary. I have intervened when the actions of strangers are clearly wrong. Several years ago, my wife, daughter and I, were walking in downtown Victoria enjoying a beautiful spring day. A man sprinted out the door of a convenience store. A woman followed, yelling for him to stop. I asked what happened. She replied he’d stolen a can of soda. I followed him, yelled at him to stop, and that I was going to call the police. He stopped, turned around, put the soda on the ground, and took off again. I returned the can of Coke to its rightful owner. More recently, I was in the check-out out counter at a grocery store. My daughter was with me. An irate customer started screaming at the employee at the customer service desk. He was horrible, insulting her personally, loudly, and using vile language. A manger asked him to leave. He didn’t. I strode over, stared him down, and, very loudly, told him to leave and to “do it now.” He left.

Looking back on the soda stealer, and the man in the grocery store, I’d do the same things again. Especially grocery store guy. His words and actions were disgusting. I’m glad I intervened. I think that was my good wolf at work.

I thought about those things as dog man and his boys waited for their subs. I kept my mouth shut. My order was done before theirs. I paid my bill and walked out. I reminded myself that you never know what is going on in someone’s life. Just because dog man’s dog wasn’t a service dog doesn’t mean that the dog wasn’t providing comfort and security that I didn’t understand – comfort and security that dog man needed in his life at that moment in time.

Or maybe dog man was just a selfish, self-centered, entitled idiot who never once considered that strangers in a restaurant didn’t want to be around his dog.

Ultimately it doesn’t matter. My instinct was to say or do something. I’m glad that I didn’t. One of the reasons is that the dozens of books I’ve read, and hundreds of podcasts I’ve listened to over the last few years, have encouraged self-reflection and a desire for self-improvement that was absent for much of my life. The wisdom of others has given me practical tools that, when I use them, can make a difference. I wish I’d had those tools a long time ago. I’m thankful I have them now.

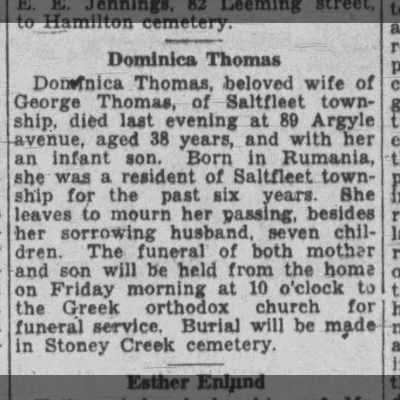

… Postscript. The accompanying photo is from a walk on the beach with my daughter. While we live a long walk, and short drive from the water, we don’t get there often. I’m always thankful when we do. … Among the most influential authors and podcasters in my life are Dan Harris (10% Happier), Rich Roll (the Rich Roll Podcast), Dr. Rangan Chatterjee (Feel Better, Live More) and Eric Zimmer (the One You Feed).